So ... what is new?

Internet in Space is not something new, there are a lot of satellites handling this job, but Starlink is something different. We are talking here about a network of 12,000 satellites (yes, you read right, it's many thousands) that fly from 350 Km to 1160 Km above our heads and route Internet traffic really fast using lasers. This sounds like the Dutch boy from Geostorm ... if you've seen the movie.

Each of the satellites will have a data bandwidth of 20Gbps, that means a combined total of 240Tbps, almost as much as the total Internet traffic of today that is 295Tbps.

It might sound Sci-Fi, but SpaceX just got the FCC approval to deploy it... And when SpaceX promises something, they usually deliver.

Even though SpaceX is not the only company that proposed something like this (OneWeb, Space Norway, Telesat, and even Facebook is looking into it as well), they're the only ones that actually have a working rocket to place the satellites in orbit. So we would put our money on them.

That many satellites sending data is very much like mesh networks from the Internet of Things that we already have, just that instead of devices, we have satellites. Even tough that for now these satellites just relay data, in the future they might provide other services. This is the first step towards the Internet of Things ... in space.

There are a lot of satellites out there used for communication services, that implies also the Internet. So what's new?

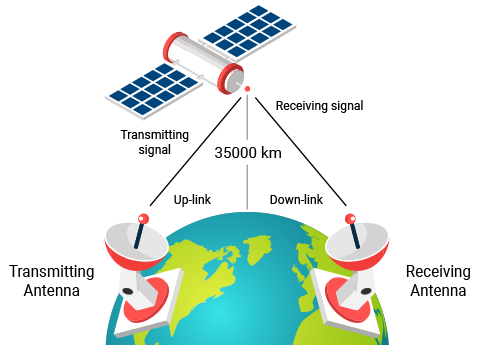

This is how we use satellites now

If you want the short version, it takes a long time to get the information up to the satellite and back down using some sophisticated equipment, mostly big antennas. If you are familiar with geostationary satellites, you might want to skip to the next section. Otherwise, just bear with us.

The deployed satellites are used mainly for mirroring, or better said, relaying. That means a ground station sends up some data to the satellite, the satellite takes the same data it got and sends it back to a different ground station in a different location. Seems easy, so ... what's the catch? Why are we still using underwater fiber optics cable and not these satellites?

To do this, the satellite is a geostationary one, meaning it travels at the same speed as the Earth rotates, so if you look at it from the ground, it appears to stay at a fixed point. Of course, the satellite moves, but so does the Earth. To achieve this kind of stability, the satellite needs to be at a distance of approximately 35,000 Km (about 11,000 miles) above.

Being so far away, the time it takes for a data signal to reach the satellite and get back to another ground station is about 240 ms. And if you think this is actually fast, try sending out a ping to google.com. The average round-trip time, or RTT, (that includes your computer, your Internet Service Provider, or ISP, server's, the underwater fiber optics cable etc., Google's servers and all the way back) is 40 ms on an LTE connection, which is 6 times faster.

There are still some advantages when having geostationary satellites, they cover a lot of ground. Being so high, geostationary satellites can cover a big part of the Earth. Only a few of them are needed to cover the whole surface. Being at a fixed point, the base station is always able to reach the satellite (sometimes it depends on the weather), so it is always on.

Starlink

Here's what SpaceX has in mind: launch a total of 11943 satellites (plus some spare ones) into Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and into VLEO (Very Low Earth Orbit) by 2027. The FCC Approval requires them to deploy 50% of the first 4425 satellites by 2024.

Step 1 launch LEO Satellites

- Start with 1600 satellites on orbit at around 1160 Km high

- Launch another 2825 satellites on orbit between 1150 Km and 1325 Km high

Here's the exact plan:

| Parameter | Initial Deployment |

Step 2 launch VLEO Satellites

- Launch 7518 satellites on orbit between 335 Km and 345 Km high

Here's the exact plan:

| Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sattelites | 2547 | 2478 | 2493 |

| Altitude | 345.6 Km | 340.8 Km | 335.9 Km |

| Inclination | 53° | 48° | 42° |

Now that's a lot of satellites ... and they're close to Earth (if you compare them with the geostationary ones, remember they fly at 35.000 Km). Just to give you an idea where they are, the International Space Station (or ISS) is at about 400 Km above Earth.

For further technical details, just take a look at the FCC Application (PDF file).

This fleet of satellites looks very futuristic and is very similar to the Internet of Things idea of sensors that we have today. This is why, we dared to call this the Internet of Space.

Tech details

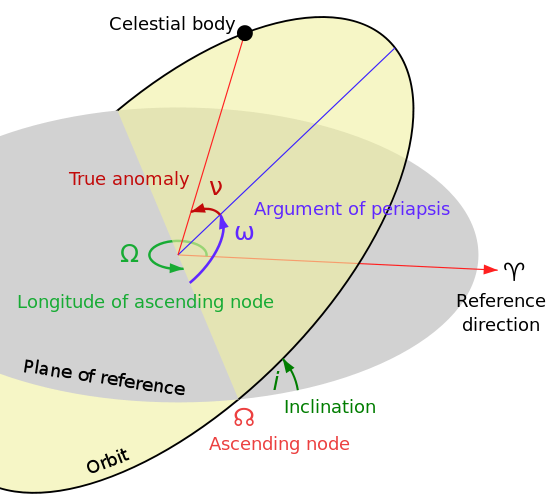

Before we can understand (or speculate) how this is going to work, we need to understand what's in those tables: altitude, orbital plane and inclination. The altitude should be self-explanatory, let's talk a few words about the orbital plane and inclination.

The Orbital Plane is an imaginary disc in which a satellite flies. Any satellite that flies around the Earth has an elliptic path (around the Earth) that can be placed into a 2-dimensional plane.

The Inclination is a little more mathematic. Now let's imagine a plane that contains the equator, the equatorial plane. This would be a plane that would split the Earth in two: the northern hemisphere and the southern hemisphere. The angle that the satellites' orbital plane makes with the equatorial plane is named the inclination.

The wikipedia picture below should explain this visually.

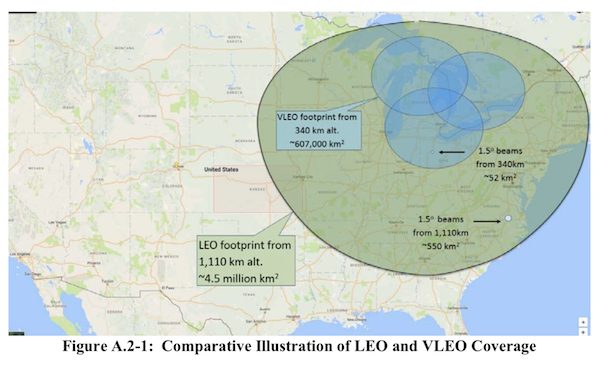

So what's different from the geostationary satellites? The coverage of a satellite and the fact that they are on the move.

Coverage: The Starlink satellites fly pretty low (still much higher than an airplane, but low in astronomical terms). This means that the ground area that a satellite may cover is limited. When we say cover, we mean the area where a ground station needs to be in order for the satellite to be able to talk to it. In an analogy, think of the area the satellite is able to photograph. For LEO satellites, the area has about a 1000 Km radius, while for the VLEO it is about 400 Km radius. That's limited! The image below, taken from the FCC Application, better shows what the coverage for a satellite is.

Movement: Satellites that are used today are geostationary, that means they are always at the same point when looked upon from Earth. Remember they move at the same speed as the Earth does. Starlink satellites are different, they are at a lower location, and in order to stay there, and not to fall down, they need to move faster. This means that they circle the Earth every 100 minutes (depending on the altitude, but the average would be that).

Now here's the problem: the surface they cover is small and they are not always present. This means that base stations:

- have to rapidly switch from one satellite to the other

- sometimes base stations will be offline (as there is no satellite in reach or there is bad weather)

- satellites will have to talk to each other a lot while each one of them is moving differently

Laser

The purpose of Starlink is to reduce latency (the time that data travels) between long distances and to offer coverage to remote areas where Internet infrastructure is hard to install (jungle, mountains, ... somebody said Alaska? ...). This is being done by setting up base stations, with antennas no larger than a pizza box and a fleet of thousands of satellites communicating with each other.

The speed of communication of Starlink comes from the usage of lasers. This is not new, as fiber optics uses lasers to transmit data. There is a tiny detail though: light travels 47% percent faster in the vacuum than in glass (the would be the fiber optics). Based on this, instead of transmitting data through cables (and pulling them into impossible areas - like under the ocean or on top of a mountain), just place a base station, connect it to the local network and to the Starlink fleet.

The base station gets the data, uploads it to the satellite it thinks it has the best connection with, the satellite lasers the data to its neighbors until it gets to a satellite in reach of the destination base station. This one downloads the date to the base station. Simple, right? Just keep in mind that these satellites are always on the move, so every minute the network (including base stations) has a different configuration. Just imagine that there is no fixed WiFi access point and you have cars with WiFi access points running around the city and your phone needs to connect to a different one every minute.

It is speculated that each satellite will have five laser connections:

- one with the satellite ahead (in the same orbital plane) - this is always on

- one with the satellite behind (in the same orbital plane) - this is always on

- one with the satellite ahead from the next orbital plane - this one is always on, but the laser has to adjust the angle, as the satellite is not always in the same place

- one with the satellite behind with the previous orbital plane - this one is always on, but the laser has to adjust the angle, as the satellite is not always in the same place

- one with the satellite that is crossing its path from a different orbital plane - this one is on and off, as it will connect for short periods of time, when another satellite is in range

This is really nice, but there are some interesting challenges that we need to overcome first. The FCC Application from SpaceX does not explain any of the functioning, so this is pure speculation. You can find more details in the research papers listed at the end of this post.

Is this really useful?

This is something that time will prove. For now, all we have are some speculations.

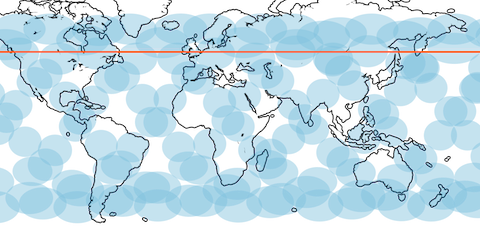

As far as the FCC Application states, already 10% of the first step's initial deployment of satellites would cover all the time the area located at the 45° parallel, probably as this is the most populated area. The second step would cover all the globe.

A study, Networking in Heaven as on Earth claims that with only these 10% of the satellites in place, there will be a big challenge in routing data. To make it able to cope with the networks that we have, a lot of bandwidth will be lost (as the connection during some time is not reliable and the routes change to fast).

Another study, Delay is Not an Option: Low Latency Routing in Space simulated that for long distances, traffic will be faster than what we have today. In some cases, it will be faster than if we would install a fiber optics cable directly between the two destinations (mostly when it comes to Africa and the southern hemisphere).

Here's what we have to figure out

There is a lot of speculation about how Starlink would work. What is absolutely sure is that there are a lot of issues that need to be figured out. Here is a short list:

- how do we route?

- how do satellites reliable communicate among them?

- what if one breaks down (SpaceX) claims it will have spare satellites in orbit).

- what will be the cost? Is it feasible?

Let's talk about some of them.

How do we route

Routing is a very important process in networking. Routing is used by routers to decide how to get the data from point A to point B using the best path. Please note that the best path might not be the shortest. It is more or less like using Waze when driving. Now here's the issue: the networks that we have today are pretty static, things don't change that frequently. From time to time there is some link that gets down, but that is it.

Now image we have a whole new network with the same capacity (remember, 12,000 satellites with a bandwidth of about 240Tbps) that changes every minute. Satellites are on the move (and in a hurry, or they fall down). This creates a lot of challenges as routes are continuously changing. Imagine Waze changing the route you should take every minute.

Base stations see a lot of satellites in range, which ones do they choose? What if some uplink data transfer fails? How does the base station retransmit it? The satellite might not be in range anymore. And here comes the weather. At the frequency these satellites use, weather becomes a factor. Interestingly enough, this will be a factor in the routing decision.

How much does it cost?

This again is a speculation. SpaceX estimates a cost of $10 billion to set up Starlink. The average exploitation time of a satellite is 5 years, that means they need to change the network. Here the cost is estimated at about $4 billion (as hardware becomes cheaper and easier to produce and launch into space). It is estimated that if SpaceX were to triple its investment from the operational income, they would have to charge an average of $0.06 per GB. This is comparable to the $0.003 to $0.03 per GB that we pay today.

More about Starlink

These papers have a lot more information about Starlink, so if you are eager to understand more, go ahead and read them:

- Gearing up for the 21st century space race

- Delay is Not an Option: Low Latency Routing in Space

- Networking in Heaven as on Earth

And there you go, instead of pulling cable (or fiber optics), just place a base station an enjoy your favorite streaming series.